Alpine Destinations & Commercial Strategy

Marketing StationDeSkiTeil 2

In the first part of our analysis we have looked at good practice in commercial sales strategies from the cruise industry. In this second part we will focus on the challenges of implementing such a strategy in Alpine destinations.

New Commercial Strategy for Alpine Destinations

It has been argued that new tourist buying expectations and behavior have changed therefore a change in the commercial strategy is needed. To adopt commercial strategies such as those implemented in the cruise industry, a consultation process is needed to assess which strategies would be mostly likely to be accepted by the different commercial operators players active in Alpine destinations.

- When implementing dynamic pricing approaches in conjunction with product bundling, there is a need to decide on how revenue will be split and profits shared amongst the various commercial stakeholders?

- Also, if a destination “revenue manager” is in charge of maximizing in-destination sales by creating products, determining price and controlling inventory availability, who would this person report to and how would the cost be covered?

Without a combined effort, such an approach would not succeed, hence there is a need to identify and, where possible, neutralize, possible barriers to success, prior to attempting implementation. Thus a series of questions and issues need to be addressed:.

- As the commercial players in the destination are often highly fragmented, it is essential to assess whether the notion of coopetition will be accepted by the relevant stakeholders, as this is deemed essential to modify the over-riding commercial strategy operating at the destination level.

- The idea would be to harness different forms of coopetition into one central organization able to maneuver the different stakeholders, dynamically manipulating the commercial offerings available to promote demand and subsequently the profit of the destination.

- The general ability of firms to harness customer intelligence data in real time is increasing while at the same time, big data tools are being developed for customers to use to find the best travel deals. Thus to be successful, a continued assessment of demand patterns, as well as behavioural customer attributes is essential, to make the right products available, to the right customers, at the right time, to optimize revenue.

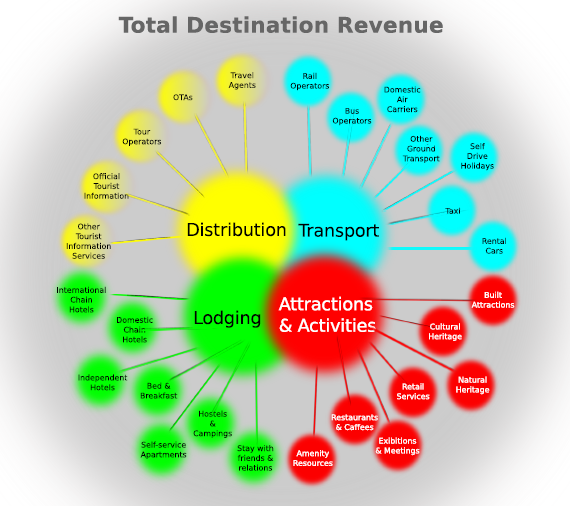

- Products offered can be considered as core or ancillary (the classification of which will be dependent on the customers’ reason to travel/stay). The new commercial strategy should aim to focus on all destination revenue streams, considering opportunities to maximize the total contribution to fixed costs, by time of day and day of the week.

As the ski pass has the potential to generate a significant source of revenues for smaller alpine destinations, this could represent the “core product” during the winter season (where achieving breakeven/maximizing sales is the goal).

The implementation of a new more cooperative commercial strategy within a traditional alpine destination may not be accepted by all stakeholders, attempts at innovating commercial strategy have had very low levels of success, even when a decline in profit is evident. Laesser et al., 2010 suggested new pricing models for cable car companies, but have not evaluated how these might be deployed in practice.

Alpine Destinations: Opportunities and Threats

Laesser et al. (2010) identified new pricing models for alpine cableway companies to adapt to contemporary challenges e.g. highly fluctuating workloads, frequent periods of excess capacity and competitive prices. These challenges often lead to significant profit erosion hence a laissez faire scenario severely limits the sustainability of cable car (and other similar) companies. Although changing the way such services are priced the study confirmed that customers now expect a fairly wide range of price variation, rewarding good behaviour (such as booking early and paying in advance) as well as providing a range of differentiated products. Contemporary consumers accept that a surcharge is payable in the case of a premium offering but expect that savings can be made where they are flexible with regards to the time of service and a willingness to share risk (of a sale/experience not materialising) with the service provider.

To conclude, price should no longer be considered the main attribute, rather the focus should be the time and intensity of the experience. Thus price differentiation and inventory control should be oriented not to purchase volume, but to time of utilisation. Laesser et al. (2010) utilised a summer and winter survey instrument to identify potential (acceptable) price percentage changes for a range of new products where tangible and intangible elements of the product are manipulated to add perceived value or to provide a sound basis for a price reduction. For example, day of the week pricing (low demand days being cheaper to encourage flexible tourists to switch the day they would like to ski from a weekday to a weekend), adding in a “complimentary” meal at the summit of the mountain (to charge more for the ski-pass), reserved parking (so tourists have a shorter walk to the lift and less hassle), a discount for early booking, a supervised activity included in the price of a ski pass (short lesson, guide, childcare). The premium offers were categorised as convenience generating offers (reserved parking spaces ) or including social (supervised) activity as well as discounted offers for those with lower levels of willingness to pay (early booking, non-refundable etc.).

The study identified that the perception of price is substantially influenced by the central infrastructural conditions (visitor facilities, slopes, hiking trails, etc.) and the quality of the interaction with service personnel (complaint handling skills, dissemination of information, customer care as well as concierges or rangers on the mountain. All pricing changes would require extensive content and comprehensive communication in the valley as well as on gondolas or chair lifts. Figure 1 shows the range of different independent offerings that that could be combined to form new dynamically priced products.

Other recent studies by Plichon (2014) and the Valais Tourism Observatory (2013) identified that the larger ski stations were better able to assimilate their high fixed costs through a high ski pass price. Skiers found the pricing fair as the larger domains present better value in terms of infrastructure and variety of ski trail. The value for money offered by smaller ski resorts was deemed inferior, due to a more limited ski domain. This is because when defining price, these ski stations use their high fixed costs as the basis to trade commercially. As these are higher, per kilometer of available ski trail (and perhaps the cableway infrastructure is less modern), smaller alpine destinations appear to offer less value for money. This perception negatively impacts their ability to attract the required volume of skiers needed to achieve breakeven point. Thus they are likely to require third party financial support and thus drain federal or regional resources, allocated to tourism. Also, the ability to renovate lifts regularly (and maintain the quality found in larger ski stations) is severely hindered due to a lack of excess profits to set aside for regular upgrades to infrastructure.

In general, the larger Swiss ski resorts appear to be priced competitively when compared with those in Austria, in France and in Italy. A comparison between the prices of top destinations in Central Europe with, for example, ski resorts in North America also revealed that the prices are on average lower than those of North America, perhaps due to local or regional competition in the Alpine region. However, the "fixed" nature of ski pass prices demonstrates that the cableway firms do not assess the perception of value that more kilometers of ski trail represent to the skier. Historically prices are determined and adapted slowly and in small steps, where the competitive behavior and perceptions of price sensitivity play a central role. According to Wicky & Vaquin, (2014) ski stations at lower altitudes have a shorter winter season due to warmer temperatures and an inability to maintain adequate snow coverage. Also, those at higher altitudes will only be able to maintain key ski runs open until the Easter period.

The last winter season resulted in a better than expected results in most alpine destinations in the Valais (Wicky & Vaquin, 2014); outcomes were expected to be catastrophic due to the lack of snow fall earlier in the season. This demonstrates the lack of risk management strategy related the dependency on snow fall and the lack of a diverse range of activities that need to be in place to attract tourists to the destination. Tourists do apply risk management to their planned holiday experiences and thus if those targeted have skiing is their primary desired activity, then they may not select smaller alpine destinations for their winter holidays.

Cableway operators must generate a critical turnover to survive economically (operation, replacement, possibly extension) in the longer term without outside help. Can this critical level of sales be determined by solely depending on available kilometer of slopes? Swiss Alpine destinations need to further develop homogenous performance measures so as to enable different size ski destinations can compare themselves to each other with a view to understand how they did and what they could do to improve their financial performance. In the short term, larger alpine destinations have the advantage but they may cease to remain competitive if the commercial stakeholders continue to operate with a fragmented commercial strategy and climate change predictions are accurate. Thus the increasing importance of coopetition (collaboration while in competition for a larger share of the customers wallet) will be explored in the last section of this article.

Stakeholders, key influencers and barriers to change, and innovation

- Collaboration and especially coopetition is increasingly important within and among destinations.

- Understanding customers is a critical further step destinations must take to successfully capture business opportunities that arise, in an environment with increased competition.

Where classical markets are changing and new target markets are emerging, collaborative and especially coopetitive attitudes can generate positive benefits for all actors involved

When tourism businesses both compete and cooperate with other companies simultaneously, a complex and dense system of inter-organizational relationships is developed. To clarify, coopetition is where competing, co-located companies also collaborate. In tourism, the shift from collaborating on a short-term basis to a long term one occurs when public and private stakeholders understand the benefits accruing to cooperation in terms of enhancement of the brand image of the destination and the attraction of a higher number of visitors, by leveraging the destination's multifaceted asset. The achievement of collaborative/coopetitive advantage’ is considered more relevant than competitive advantage as .collaboration between destinations can be instrumental to improve the value of a supra-national territory, creating benefits for both residents and visitors (Mariani et al., 2014). Cooperative behavior in tourism destination communities is a condition for sustainable planning and development. Partnerships can be cemented via formal, contract-based agreements as well as informal, relation-based cooperation occurring jointly or in substitution, depending on the context and the subject of research have been tested within tourist destination communities (Beritelli, 2011).

Conclusion

Some tourism sectors have reacted to the evolving competitive environment by being nimble, flexible and innovative in their sales and revenue optimization strategies. In particular, the cruise line industry was scrutinized as mostly closely resembles a tourist destination.

Cruise lines enjoy average cabin occupancy rates more than 36 percentage points higher than those of hotels. They have empowered their travel agents to be loyal partners in what has become a very efficient distribution network. These travel agents are an essential arm of their cabin-inventory management strategy, from making individual as well as group reservations, collecting the deposits and full payments, tracking down late arrivals, and conducting silent auctions when the system breaks down and the cruise ships are oversold.

The broader tourism sector has increased capacity utilization by introducing yield management, distribution channel management, customer relationship management under the umbrella management concept known as revenue management. Further, the optimization of total revenue achieved from available square meter of commercial space will the focus going forward. Also, measures are in place to ensure revenue increases augment profit generated.

Tourism destination actors each possess the conditions required to implement revenue management effectively (perishable inventory, ability to segment, generate advance sales, low marginal sales cost, high production cost) and by cooperating, they could generate far greater returns from the various spaces and services offered.

In (smaller) Alpine resorts, a new commercial strategy is needed using coopetition to raise the competitiveness/attractiveness of Alpine products. Recent studies analysed the competitiveness of different size Alpine destinations and suggested new pricing models. These did not however evaluate how to implement such changes in practice. To avoid alienating influential stakeholders, there is a need to evaluate barriers to implementation and to identify best practice application.

Bibliography

Beritelli, P. (2011). Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(2), 607-629.

Laesser C., Bieger T., Riklin T., Engeler, I., Boksberger P. (2010) Neue Preismodelle für Bergbahnen - Konzeptionelle Grundlagen und empirische Erkenntnisse. Management Summary (February). Accessed March 20th from https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/export/DL/69370.pdf

Mariani M., Buhalis D, Longhi C, Vitouladiti O., (2004) Managing change in tourism destinations: Key issues and current trends. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2: 269–272

Observatoire Valaisan du Tourisme (2013) Big is beautiful: Preisvergleich Tageskarten in alpinen Skigebieten (CH, F, I, A) im Verhältnis zur Anzahl Pistenkilometer. Accessed May 2014.

Plichon D. (2014) Ski : quel est le forfait le moins cher au kilomètre? Paris Match 16th February. Available here. Accessed July 2014

Wicky, J., Vaquin, D. (2014) Ce printemps Bourreau et Sauver de L’Hiver. Le Nouvelliste March 28th, pages 4-5.